-

.

C'E' UN PARCO IN PARADISO

RINASCE L'EDEN

Nelle paludi fra i fiumi Tigri ed Eufrate, dove la mitologia vuole siano vissuti Adamo ed Eva, è nato il primo Parco nazionale iracheno.

Un grande avvenimento simbolico e ambientale: la zona era stata infatti prosciugata da Saddam.

In un Paese in cui caos e violenze sembrano non finire mai, la nascita di un parco nazionale è uno di quegli avvenimenti che fanno notizia.

Il parco, nato a luglio, è il primo in Iraq: si chiama "Parco nazionale delle paludi mesopotamiche" e rappresenta la tappa finale di un processo di ripristino dell'ambiente naturale iniziato nel 2006.

La zona ha anche un valore simbolico, perché il luogo è carico di significato per la nostra cultura: è il biblico giardino dell'Eden!

L'area è infatti ritenuta il luogo dove Adamo ed Eva vissero prima di essere scacciati dal Paradiso Terrestre.

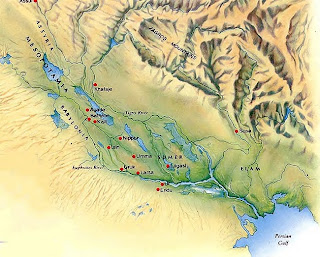

Le paludi, area ricca di vegetazione ed animali, erano situate tra i fiumi Tigri ed Eufrate e coprivano 15.000 Km quadrati.

STORIA RECENTE

Nel secolo scorso l'area era abitata da mezzo milione di "Arabi delle paludi", una popolazione di Sciiti: Il prosciugamento iniziò negli anni '50, ma fu durante il regime di Saddam Hussein che l'azione fu particolarmente feroce.

Il rais, per combattere questa popolazione ritenuta nemica, ridusse l'area allagata a non più dell'8-10% della superficie originaria.

Dietro lo sforzo di far risorgere le paludi c'è l'ingegner Azzam Alwash, fondatore dell'organizzazione non governativa "Nature Iraq".

Rifugiatosi negli Stati Uniti durante la dittatura, Alwash ha lottato anni per far capire al mondo quanto questo ambiente fosse importante, vincendo anche il Premio Goldman 2013 ( Il cosiddetto Nobel verde).

Fonte "Focus" 2013

Iraq's Garden of Eden: Restoring the Paradise that Saddam Destroyed

By Samiha Shafy

Saddam Hussein drained the unique wetlands of southern Iraq as a punishment to the region's Marsh Arabs who had backed an uprising. Two decades later, one courageous US Iraqi is leading efforts to restore the marshes. Not even exploding bombs can deter him from his dream.

Azzam Alwash is an anomaly in Iraq, a country devastated by war and terrorism. As he punts through the war zone in a wooden boat, his biggest concerns are a missing otter, poisoned water and endangered birds. Who thinks about the environment in southern Iraq, and who is willing to risk his life to save a marsh?

"Isn't this wonderful?" Alwash asks as his boat, accompanied by armed guards, glides through a channel lined with reeds. Flocks of birds fly through a reddish evening sky above the marshland, where the air temperature has dropped to 35 degrees Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit) -- cool by local standards. Basra, a city devastated by war, is only 60 kilometers (37 miles) away, and yet it might as well be on another planet.

Water buffalo snort as they swim past the boat. Alwash, a broad-shouldered man with bushy gray hair and a moustache, is beaming as he sits upright on the rowing bench. "Just look at this," he says. "There was a desert here just a few months ago."The Cradle of Civilization

Alwash, 52, a citizen of Iraq and the United States, is a hydraulic engineer and the director of Nature Iraq, the country's first and only environmental organization. He founded the organization in 2004 together with his wife Suzanne, an American geologist, with financial support from the United States, Canada, Japan and Italy. His goal is to save a largely dried-up marsh in southern Iraq. In return for giving up his job in California, Alwash is now putting his safety and health at risk.

Nowadays he spends a lot of time flying from one continent to another. Four days ago, he traveled from Fullerton, California, where his family lives, to Amman, Jordan to meet with former Iraqi Prime Minister Ayad Allawi. Then he flew to Basra to attend a conference, and now he is back in the marsh. His next stop is Baghdad, where he has an appointment at the Environment Ministry. After that, he will travel to Sulaymaniyah in northern Iraq, where, for security reasons, Nature Iraq has its headquarters. After that, he has meetings scheduled with donors and advisers in the Italian cities of Padua and Venice. Other men have a mistress, says Alwash -- he has the marshes.

Of course, this isn't just any old marsh. Alwash is fighting for a marsh which Biblical scholars believe is the site of the Garden of Eden, and which some describe as the cradle of civilization. The Mesopotamians settled in the fertile region in the fifth millenium B.C., and within a few centuries it had become the site of an advanced Sumerian civilization. Scholars believe that cuneiform was invented in the region, as were literature, mathematics, metallurgy, ceramics and the sailboat.

Only 20 years ago, an amazing aquatic world thrived in the area, which is in the middle of the desert. Larger than the Everglades, it extended across the southern end of Iraq, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers divide into hundreds of channels before they come together again near Basra and flow into the Persian Gulf. For environmentalists, this marshland was a unique oasis of life, until the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, a Sunni, had it drained in the early 1990s after a Shiite uprising.Turning the Garden of Eden into Hell

The official explanation was that the land was being reclaimed for agriculture. The military was sent in to excavate canals and build dikes to conduct the water directly into the Gulf. The despot, proud of his work of destruction, gave the canals names like Saddam River and Loyalty to the Leader Canal.

In truth, Saddam was not interested in the farmers. His real goal was to harm the Madan, also known as the Marsh Arabs. For thousands of years, the marshes had been the homeland of this ethnic group and their cows and water buffalo. They lived in floating huts made of woven reeds and spent much of their time in wooden boats, which they guided with sticks along channels the buffalo had trampled through the reeds. They harvested reeds, hunted birds and caught fish.

When the fishermen backed a Shiite uprising against the dictator, the vindictive Saddam turned their "Garden of Eden" into a hell. He had thousands of the Marsh Arabs murdered and their livestock killed. Any remaining water sources were poisoned and reed huts burned to the ground. Many people fled across the border into Iran to live in refugee camps, while others went to the north and tried to survive as day laborers. By the end of the operation, up to half a million people had been displaced.

Within a few years, the marshland had shrunk to less than 10 percent of its original size. In a place that was once teeming with wildlife -- wild boar, hyenas, foxes, otters, water snakes and even lions -- the former reed beds had been turned into barren salt flats, poisoned and full of land mines. In a 2001 report, the United Nations characterized the destruction of the marshes as one of the world's greatest environmental disasters.'Wait Until You See the Marshes'

On June 18, 2003, only three months after the American invasion, Alwash flew from Los Angeles to his native Iraq. He knew what to expect. "Nevertheless, it was a shock," he says. "I remembered water and green vegetation as far as the eye could see, but what I saw was nothing but desert, dust and the ruins of settlements."

At that point, Alwash had not stepped on Iraqi soil in exactly 24 years and 341 days. He had gone to the United States to study and eventually became an American through and through. He had an American wife, two young daughters with whom he did not speak Arabic, a house in Long Beach and a well-paid job as a hydraulic engineer. "It was the perfect American dream," he says today.

But he couldn't forget the marshland, his childhood paradise. His father, who had worked in Iraq's Water Ministry until the early 1980s, had often taken him along when he was traveling in the marshes for work or hunting geese in the reeds. Sometimes his mother and his two sisters came along on their extended outings in the boat. Alwash had promised himself that one day he would show his wife and his daughters the "Garden of Eden" of his childhood. "This is nothing," he would say when they were hiking or canoeing in California. "Just wait until you see the marshes!"

It was this promise that prompted Alwash to return to Iraq and raise funds for his plan, which involved the controlled flooding of former marshland. He and his collaborators called their ambitious plan the "Eden Again" project.

Curtis Richardson, an ecologist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, was part of the project from the very beginning, making research trips to the region between 2003 and 2007. "I've studied wetlands for my entire professional life," says Richardson, "but this marshland is the Holy Grail -- the Garden of Eden."

Soon, however, Richardson was forced to realize how naïve his enthusiasm had been. He spent many a sleepless night on the floor of his hotel room in Basra listening to the sound of gunshots outside. Heavily armed guards had to escort him during his field work. "You do feel a little strange when you're holding a pH monitor in your hand while everyone else is carrying a machine gun," he says.

Once, when Richardson went into the water near the Iranian border to take some samples, his translator, who was standing on the shore, suddenly began shouting and waving his arms wildly. "I had walked into a minefield," Richardson says. That was the moment he decided to abandon his field work.

"Azzam is fighting a courageous battle, but he needs help," says Richardson. The United States has cancelled its financial support for the project, and now most of its funding and scientific advice comes from Italy. Richardson estimates that no more than 30 to 40 percent of the former marshland can be transformed into a functioning ecosystem in the long term. But even that would represent an enormous improvement, not just for nature but also for Iraq's future.Influencing the Climate

Because they retain the water from the rivers, the marshes could prove to be an important water source for the south. They also influence the climate. The region became hotter after the marshland was destroyed, says Richardson. When temperatures went over 50 degrees Celsius (112 degrees Fahrenheit), the crops dried up in the fields. The fishermen and shrimp growers also saw a sharp decline in their catch, because the marshes were no longer there to filter dirt and pollutants out of the rivers.

Now, about a third of the original river marshes are covered with water once again. Teams of international experts, Nature Iraq employees and representatives of three Iraqi ministries are demolishing dams, channeling water from the canals back into parched areas, sowing native plants and studying the composition of species and the development of plant and animal populations.

Before they flood a new area, the scientists measure salt and sulfur concentrations in the soil. Levels are so high in some places that neither reeds nor indigenous fish species can survive. A constant flow of fresh water is needed to flush out the salt and allow the soil to recover.

Alwash and his collaborators are developing a plan for the country's first national park: a protected zone of about 1,000 square kilometers (386 square miles) where the water supply will be regulated with a large number of floodgates. "We are in the process of drafting guidelines for nature reserves," says Giorgio Galli of Studio Galli Ingegneria Spa, an engineering firm in Padua, Italy. "This sort of thing has not existed in Iraq until now." The scientists hope that if the project materializes, it could be declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.Bombs 'Just Part of Daily Life'

But all of this is happening in the midst of a conflict zone. Dozens of employees of the project have died in terrorist attacks in the last seven years. Others, fearing for their lives, have left. Experts with the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) can only provide advice from afar. For safety reasons, they have been barred from entering Iraq since 22 people died in an attack on the UN headquarters building in Baghdad in August 2003.

The situation seems to have calmed down somewhat recently. Basra is not as safe as Sulaymaniyah, but neither is it as dangerous as Baghdad. But security is a relative concept. Is the risk worth it? Can conservation even function in a country like this?

Alwash is used to bombs going off. "As long as you are at least 100 meters (about 330 feet) away, it's just part of daily life." He tries to explain how he feels: "For the first time in my life, I have the feeling that my work really helps people, and that I'm not just working to make money for my family and myself. That's fulfilling."

Nowadays, when Awash is traveling in the marsh of hope, he sometimes encounters images of his childhood. In Al-Hammar, a labyrinth of waterways leads through dense, meter-high reeds and comes together to form larger lakes. Dewdrops glisten on the reeds, rustling as they recede alongside the passing boat. A crescent moon fades away as the sun grows stronger. Tiny fish dash through the water, fleeing a water snake. And the birds are back: night herons, pied kingfishers, purple herons, little grebes, black-tailed godwits and marbled ducks.

Reed huts surrounded by sleepy water buffalo stand on small islands. Men and women with sunburned faces and long robes glide through the water in boats, cutting reeds, occasionally raising their hands in greeting.

The water has brought back the Madan, whose numbers are already believed to have climbed to about 80,000. Their stories are like the story of Naim Aatai, a small, hunched-over man with a white beard, a furrowed face and deep-set eyes. "Saddam's soldiers came to our village and accused us of hiding terrorists," says Aatai. "They shot at us and killed my brother. Then they burned down our huts."

After the attack, Aatai fled to the north and found work on a farm near Baghdad. "It wasn't a good life," he says. "It's better here. This is our home."

Dhwia Jift is just returning from her first reed-cutting trip of the day, her boat filled with reeds. A few men load the bundles onto a truck. Jift is paid the equivalent of $4 (about €3) for a full load. The slight woman, dressed in black, says that she gets up every morning before sunrise, bakes flatbread and feeds the children. Then she spends the rest of the day harvesting reeds.

The skin on her hands and feet is cracked and covered with calluses. She says that she is tired and sick, but that she doesn't want to complain. Her time as a day laborer in the north was much worse, she says, because she was treated like a slave there. "I'm free here," she says with a smile, exposing the gaps in her teeth. "At least I don't have to beg, as long as I have water and reeds."Wasting Water

But it is far from certain that the water will remain in the marshes. Turkey, where the Tigris and the Euphrates originate, is building dams and gradually reducing the flow of water southward. There are no agreements between the two countries over joint use of the rivers. And Turkey is only one of three countries, along with China and Burundi, that have not signed the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses.

Much would be gained if Iraq's farmers would learn to be economical with their use of water. They are not familiar with the principle of drip irrigation. Instead, they still flood their fields, a method that was practiced in times when there was a surplus of water.

There are also other ways to save water. Iraq treats hardly any of its sewage, and recycling water is practically unheard of. As a result, the water that is being fed out of the canals and back into the marshes contains high concentrations of fertilizer, environmental toxins and pathogens. The Environment Ministry and Nature Iraq are jointly monitoring the situation to gauge the effects on the ecosystem and the health of human beings and animals.The Hazards of Oil

Broder Merkel of the Freiberg University of Mining and Technology sits between muscular bodyguards in the lobby of the newly opened Mnawi Basha Hotel in Basra. The German hydrogeologist has identified another hazard: oil. "The oil companies can't wait to start drilling for oil in the marshes," he says. "And when that gets going, without regulations, research and monitoring, you can forget about the marshes once and for all."

Iraq has the world's third-largest oil reserves, and there are plans to triple production in the next five years. A number of oil fields are located in the marshlands. Merkel, who has short white hair and many laugh lines, has come to Basra on behalf of the German Academic Exchange Service to develop two new courses of study together with representatives of Iraqi universities: "Sustainable Oil Production" and "Hydrogeology and Water Management in Arid Regions."

This time, Merkel wants to take home a few water samples from the Basra canals. His trip takes him past slums the color of brown mud, mountains of garbage and checkpoints. The streets of Basra are filled with the stench of garbage and gasoline. Rickety cars squeeze past donkey carts and beggars. Combat vehicles are parked next to corrugated metal huts where vendors sell fruit and vegetables. Shiite mourning flags flutter in the wind. Wherever the scientists stop, police officers join them and wait politely until the guest from Germany has filled his test tubes.Hotels and Hikers

Alwash knows the geologist from Freiberg, and the two men greet each other in the Arabic fashion, by kissing each other on both cheeks. But the US Iraqi doesn't share his German colleague's pessimism. In fact, he sees the oil boom as an opportunity. "Maybe we can create incentives for the oil companies to contribute to the establishment of a nature reserve in return," says Alwash.

Alwash isn't afraid of dreaming. And when he glides through his beloved marshlands in a boat during the evening, his dream seems within reach. "I see floating reed hotels and camping sites," he says. "I see glass-bottomed kayaks, hikers, paragliders and hot-air balloons." His minders listen to him, their weapons lowered.

"The first people to come will be the ornithologists," Alwash continues. "Then the people who are interested in archaeology, in the ancient cities of Ur and Uruk. And then the eco-tourists." Eco-tourists? Alwash grins, and then he says: "One of my strengths is that I don't let myself be constrained by reality."

http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/...d-a-709866.html

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@traduzione google@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Giardino dell'Iraq dell'Eden: Ripristino del Paradiso che Saddam Distrutto

By Samiha Shafy

Saddam Hussein prosciugato zone umide uniche del sud dell'Iraq come una punizione per Marsh arabi della regione, che aveva appoggiato una rivolta. Due decenni più tardi, un coraggioso US iracheno sta portando gli sforzi per ripristinare le paludi. Nemmeno esplodere le bombe lo può dissuadere dal suo sogno.

Azzam Alwash è un'anomalia in Iraq, un paese devastato dalla guerra e dal terrorismo. Come egli sterline attraverso la zona di guerra in una barca di legno, le sue maggiori preoccupazioni sono una lontra mancante, acqua avvelenata e uccelli in via di estinzione. Chi pensa che l'ambiente nel sud dell'Iraq, e che è disposto a rischiare la vita per salvare una palude?

"Non è meraviglioso?" Alwash chiede come la sua barca, accompagnato da guardie armate, scivola attraverso un canale fiancheggiato da canneti. Stormi di uccelli volano in un cielo rossastro sera sopra la palude, in cui la temperatura dell'aria è scesa a 35 gradi Celsius (95 gradi Fahrenheit) - freddo per gli standard locali. Bassora, una città devastata dalla guerra, è a soli 60 chilometri (37 miglia) di distanza, e tuttavia potrebbe anche essere su un altro pianeta.

Bufalo sbuffo mentre nuotano davanti alla barca. Alwash, un uomo dalle spalle larghe, con i capelli grigi e folti baffi, è raggiante come si siede in posizione verticale sul banco di canottaggio. "Basta guardare a questo", dice. "C'è stato un deserto qui a pochi mesi fa."

La culla della civiltà

Alwash, 52, un cittadino di Iraq e Stati Uniti, è un ingegnere idraulico e il direttore di Nature Iraq, prima e unica organizzazione ambientale del paese. Ha fondato l'organizzazione nel 2004 insieme con la moglie Suzanne, un geologo americano, con il sostegno finanziario degli Stati Uniti, Canada, Giappone e Italia. Il suo obiettivo è quello di salvare una gran parte prosciugato paludi nel sud dell'Iraq. In cambio della rinuncia il suo lavoro in California, Alwash sta ora mettendo la sicurezza e la salute a rischio.

Al giorno d'oggi si spende un sacco di tempo a volare da un continente all'altro. Quattro giorni fa, ha viaggiato da Fullerton, California, dove abita la sua famiglia, a Amman, Giordania per incontrarsi con l'ex primo ministro iracheno Ayad Allawi. Poi è volato a Bassora per partecipare a una conferenza, e ora è di nuovo nella palude. La sua prossima tappa è a Baghdad, dove ha un appuntamento presso il Ministero dell'Ambiente. Dopo di che, egli si recherà a Sulaimaniya, nel nord dell'Iraq, dove, per motivi di sicurezza, Nature Iraq ha il suo quartier generale. Dopo di che, egli ha in programma incontri con i donatori e consulenti nelle città italiane di Padova e Venezia. Altri uomini hanno un amante, dice Alwash - ha le paludi.

Naturalmente, questo non è solo una vecchia palude. Alwash si batte per una palude che gli studiosi della Bibbia ritengono che è il sito del Giardino dell'Eden, e che alcuni descrivono come la culla della civiltà. I mesopotamici si stabilirono nella regione fertile nel quinto millennio aC, e nel giro di pochi secoli era diventata la sede di una civiltà sumera avanzato. Gli studiosi ritengono che cuneiforme è stato inventato nella regione, così come la letteratura, la matematica, la metallurgia, la ceramica e la barca a vela.

Solo 20 anni fa, un mondo acquatico incredibile prosperato nella zona, che si trova nel bel mezzo del deserto. Più grandi delle Everglades, si estendeva in tutta la parte meridionale dell'Iraq, dove i fiumi Tigri ed Eufrate si dividono in centinaia di canali prima di venire di nuovo insieme nei pressi di Bassora e sfociano nel Golfo Persico. Per gli ambientalisti, la palude era un oasi di vita, fino a quando il dittatore iracheno Saddam Hussein, sunnita, lo fece seccare nei primi anni 1990, dopo una rivolta sciita.

Girando il Giardino dell'Eden in inferno

La spiegazione ufficiale è che il terreno era stato recuperato per l'agricoltura. Il militare è stato inviato a per scavare canali e costruire dighe per condurre l'acqua direttamente nel Golfo. Il despota, orgoglioso del suo lavoro di distruzione, ha dato i nomi di canali come Saddam fiume e fedeltà al Canale di Leader.

In verità, Saddam non era interessato agli agricoltori. Il suo vero obiettivo era quello di danneggiare la Madan, noto anche come gli arabi delle paludi. Per migliaia di anni, le paludi erano state la patria di questo gruppo etnico e le loro mucche e bufali d'acqua. Vivevano in capanne galleggianti fatte di canne intrecciate e ha trascorso gran parte del loro tempo in barche di legno, che hanno guidato con bastoni lungo i canali il bufalo aveva calpestato attraverso le canne. Hanno raccolto le canne, uccelli cacciati e pesce pescato.

Quando i pescatori salvati una rivolta sciita contro il dittatore, il vendicativo Saddam trasformato il loro "Giardino dell'Eden" in un inferno. Aveva migliaia di arabi Marsh assassinati e il loro bestiame uccisi. Eventuali fonti di acqua rimanenti sono stati avvelenati e capanne di canne rase al suolo. Molte persone sono fuggite oltre confine, in Iran a vivere in campi profughi, mentre altri sono andati al nord e hanno cercato di sopravvivere come braccianti. Entro la fine dell'operazione, fino a mezzo milione di persone erano stati spostati.

Nel giro di pochi anni, la palude si era ridotto a meno del 10 per cento della sua dimensione originale. In un luogo che una volta era brulicante di fauna selvatica - cinghiali, iene, volpi, lontre, serpenti d'acqua e persino leoni - le ex canneti erano state trasformate in saline sterili, avvelenato e pieno di mine terrestri. In un rapporto del 2001, l'ONU ha caratterizzato la distruzione delle paludi come uno dei più grandi disastri ambientali del mondo.

'Aspettate di vedere il Padule'

Il 18 giugno del 2003, solo tre mesi dopo l'invasione americana, Alwash volato da Los Angeles a sua nativa Iraq. Lui sapeva cosa aspettarsi. "Tuttavia, è stato uno shock," dice. "Mi sono ricordato di acqua e la vegetazione verde a perdita d'occhio, ma quello che ho visto non era altro che deserto, la polvere e le rovine di insediamenti".

A quel punto, Alwash non aveva fatto un passo sul suolo iracheno in esattamente 24 anni e 341 giorni. Si era recato negli Stati Uniti per studiare e alla fine divenne un americano tutto e per tutto. Aveva una moglie americana, due giovani figlie con cui non parlava arabo, una casa a Long Beach e un lavoro ben pagato come ingegnere idraulico. "E 'stato il sogno perfetto americano", dice oggi.

Ma non poteva dimenticare la palude, il suo paradiso infanzia. Suo padre, che aveva lavorato nel Ministero acqua iracheno fino ai primi anni 1980, avevano spesso lo prese con sé quando era in viaggio nelle paludi per lavoro o oche da caccia tra le canne. A volte la madre e le sue due sorelle è arrivato il loro uscite estesi nella barca. Alwash aveva promesso a se stesso che un giorno avrebbe mostrato la sua moglie e le sue figlie "Giardino dell'Eden" della sua infanzia. "Questo è niente," diceva quando sono stati escursioni a piedi o in canoa in California. "Aspetta fino a vedere le paludi!"

E 'stata questa promessa che ha spinto Alwash di tornare in Iraq e raccogliere fondi per il suo progetto, che ha coinvolto l'inondazione controllata di tempo paludose. Lui ei suoi collaboratori chiamato il loro piano ambizioso il progetto "Eden Again".

Curtis Richardson, un ecologista alla Duke University di Durham, North Carolina, è stato parte del progetto fin dall'inizio, facendo viaggi di ricerca nella regione tra il 2003 e il 2007. "Ho studiato le zone umide per tutta la mia vita professionale", dice Richardson, "ma questa palude è il Santo Graal -. Del Giardino dell'Eden"

Ben presto, però, Richardson è stato costretto a rendersi conto di quanto ingenuo il suo entusiasmo era stato. Ha trascorso molte notti insonni sul pavimento della sua camera d'albergo a Bassora ascoltando il suono di spari fuori. Guardie pesantemente armate hanno dovuto scortarlo durante il suo lavoro sul campo. "Ci si sente un po 'strano quando si è in possesso di un monitor di pH in mano mentre tutti gli altri sta portando una mitragliatrice," dice.

Una volta, quando Richardson è andato in acqua vicino al confine iraniano a prendere alcuni campioni, il suo traduttore, che stava in piedi sulla riva, cominciò improvvisamente gridando e agitando le braccia all'impazzata. "Ero entrato in un campo minato", dice Richardson. Quello era il momento in cui ha deciso di abbandonare il suo lavoro sul campo.

"Azzam sta combattendo una battaglia coraggiosa, ma ha bisogno di aiuto", dice Richardson. Gli Stati Uniti hanno cancellato il suo sostegno finanziario per il progetto, e ora la maggior parte del suo finanziamento e la consulenza scientifica viene da Italia. Richardson stima che non più del 30 al 40 per cento del tempo paludose può essere trasformato in un ecosistema funzionante nel lungo termine. Ma anche questo rappresenterebbe un enorme miglioramento, non solo per la natura, ma anche per il futuro dell'Iraq.

Influenzare il Clima

Perché conservano l'acqua dei fiumi, le paludi potrebbe rivelarsi una fonte d'acqua importante per il sud. Essi influenzano anche il clima. La regione è diventata più calda dopo la palude è stato distrutto, dice Richardson. Quando le temperature sono andati oltre i 50 gradi Celsius (112 gradi Fahrenheit), le colture prosciugato nei campi. I pescatori e coltivatori di gamberi ha visto anche un forte calo della loro cattura, perché le paludi non erano più lì per filtrare lo sporco e le sostanze inquinanti fuori dei fiumi.

Ora, circa un terzo delle paludi del fiume originali sono coperti con l'acqua ancora una volta. Squadre di esperti internazionali, dipendenti Nature Iraq e rappresentanti dei tre ministeri iracheni stanno demolendo dighe, canalizzazione dell'acqua dai canali di nuovo in zone aride, piante autoctone semina e studiare la composizione delle specie e lo sviluppo delle popolazioni vegetali e animali.

Prima che inondano di una nuova area, la misura di scienziati sale e le concentrazioni di zolfo nel suolo. I livelli sono così alti in alcuni posti che né canne né specie di pesci autoctone possono sopravvivere. È necessario un flusso costante di acqua fresca per irrigare il sale e permettere al terreno di recuperare.

Alwash ei suoi collaboratori stanno mettendo a punto un piano per il primo parco nazionale del paese: una zona protetta di circa 1.000 chilometri quadrati (386 miglia quadrate), in cui la fornitura di acqua sarà regolato con un gran numero di paratoie. "Siamo nel processo di elaborazione di linee guida per le riserve naturali", afferma Giorgio Galli di Studio Galli Ingegneria SpA, una società di ingegneria a Padova, Italia. "Questo genere di cose non è esistito in Iraq fino ad ora." Gli scienziati sperano che se il progetto si materializza, potrebbe essere dichiarato patrimonio dell'umanità dall'UNESCO.

«Solo parte della vita quotidiana 'Bombs

Ma tutto questo sta accadendo nel bel mezzo di una zona di conflitto. Decine di dipendenti del progetto sono morte in attentati terroristici degli ultimi sette anni. Altri, temendo per la propria vita, hanno lasciato. Gli esperti con il Programma Ambiente delle Nazioni Unite (UNEP) in grado di fornire solo consigli da lontano. Per motivi di sicurezza, sono stati vietato l'ingresso Iraq dal 22 persone sono morte in un attentato al quartier generale delle Nazioni Unite a Baghdad nell'agosto 2003.

La situazione sembra essersi calmata un po 'poco. Bassora non è sicuro come Sulaimaniya, ma non è nemmeno così pericoloso come Baghdad. Ma la sicurezza è un concetto relativo. È il rischio vale la pena? Può conservazione funzionare anche in un paese come questo?

Alwash è usato per le bombe che si spengono. "Finché si è almeno 100 metri (circa 330 piedi) di distanza, è solo una parte della vita quotidiana." Egli cerca di spiegare come si sente: "Per la prima volta nella mia vita, ho la sensazione che il mio lavoro aiuta davvero le persone, e che non sto solo lavorando per fare i soldi per la mia famiglia e me stesso Questo è appagante.».

Al giorno d'oggi, quando Awash è in viaggio nella palude di speranza, a volte incontra le immagini della sua infanzia. In Al-Hammar, un labirinto di corsi d'acqua si snoda attraverso fitti, alti un metro canne e viene fornito insieme a formare laghi più grandi. Gocce di rugiada brillano sulle canne, fruscianti come si ritirano a fianco della barca passando. Una falce di luna svanisce come il sole diventa più forte. Piccolo dash pesce attraverso l'acqua, in fuga un serpente d'acqua. E gli uccelli sono tornati: nitticore, martin pescatori, aironi pied viola, piccoli svassi, pittime e anatre marmorizzate.

Reed capanne circondate da bufalo assonnato stanno su piccole isole. Uomini e donne con i volti bruciati dal sole e lunghi abiti scivolano attraverso l'acqua in barca, tagliando le canne, a volte alzando la mano in segno di saluto.

L'acqua ha riportato la Madan, il cui numero è già creduto di aver salito a circa 80.000. Le loro storie sono come la storia di Naim Aatai, un uomo piccolo e ingobbita con la barba bianca, un viso solcato e gli occhi infossati. "I soldati di Saddam sono venuti al nostro villaggio e ci hanno accusato di nascondere i terroristi", dice Aatai. "Hanno sparato a noi e hanno ucciso mio fratello. Poi hanno bruciato le nostre capanne."

Dopo l'attacco, Aatai fuggito al nord e trovò lavoro in una fattoria nei pressi di Baghdad. "Non è stata una buona vita," dice. "E 'meglio qui. Questa è la nostra casa."

Dhwia Jift sta solo tornando dal suo primo viaggio Reed-taglio della giornata, la barca piena di canne. Alcuni uomini caricano i pacchi su un camion. Jift è pagato l'equivalente di $ 4 (circa € 3) per il pieno carico. Il leggero donna, vestita di nero, dice che si alza ogni mattina prima dell'alba, cuoce piadina e alimenta i bambini. Poi si passa il resto delle canne di raccolta al giorno.

La pelle delle mani e dei piedi è rotto e coperto con calli. Lei dice che è stanco e malato, ma che lei non vuole lamentarsi. Il suo tempo come operaio giorno nel nord era molto peggio, dice, perché è stata trattata come una schiava lì. "Sono libero qui," dice con un sorriso, esponendo le lacune tra i denti. "Almeno io non ho a mendicare, a patto che io ho l'acqua e canne."

Sprecare acqua

Ma non è affatto certo che l'acqua resterà nelle paludi. Turchia, dove il Tigri e l'Eufrate nascono, è la costruzione di dighe e di ridurre gradualmente il flusso di acqua verso sud. Non esistono accordi tra i due paesi oltre l'uso congiunto dei fiumi. E la Turchia è solo uno dei tre paesi, insieme a Cina e Burundi, che non hanno firmato la Convenzione ONU 1997 sulla legge degli usi diversi dalla navigazione dei corsi d'acqua internazionali.

Molto si potranno ottenere se gli agricoltori iracheni avrebbe imparato a essere economico con l'uso di acqua. Non hanno familiarità con il principio di irrigazione a goccia. Invece, ancora inondano i loro campi, un metodo che è stato praticato in tempi in cui c'era un surplus di acqua.

Ci sono anche altri modi per risparmiare acqua. Iraq tratta quasi nessuna delle sue acque reflue, acqua e riciclo è praticamente sconosciuto. Come risultato, l'acqua che viene alimentato fuori dei canali e indietro nella palude contiene alte concentrazioni di fertilizzante, tossine ambientali e agenti patogeni. Il Ministero dell'Ambiente e della Natura Iraq stanno monitorando congiuntamente la situazione per valutare gli effetti sull'ecosistema e la salute degli esseri umani e degli animali.

I rischi di Olio

Broder Merkel della Freiberg Università di arte mineraria e la tecnologia si trova tra guardie del corpo muscolari nella hall della nuova apertura Mnawi Basha hotel a Bassora. L'idrogeologo tedesco ha identificato un altro pericolo: l'olio. "Le compagnie petrolifere non vedo l'ora di iniziare l'estrazione del petrolio nelle paludi," dice. "E quando questo ottiene andando, senza regole, di ricerca e di monitoraggio, è possibile dimenticare le paludi una volta per tutte."

L'Iraq ha riserve di petrolio terzo più grande del mondo, e ci sono piani per triplicare la produzione entro i prossimi cinque anni. Un certo numero di giacimenti di petrolio si trovano nelle paludi. Merkel, che ha pochi capelli bianchi e molte linee di ridere, è venuto a Bassora per conto del Servizio Tedesco di Scambio Accademico di sviluppare due nuovi corsi di studio, insieme con i rappresentanti delle università irachene: "Produzione sostenibile Oil" e "Idrogeologia e gestione delle acque in regioni aride. "

Questa volta, la Merkel vuole portare a casa un paio di campioni di acqua dai canali Bassora. Il suo viaggio lo porta baraccopoli passate il colore del fango marrone, montagne di spazzatura e posti di blocco. Le strade di Bassora sono riempiti con la puzza di spazzatura e benzina. Automobili sgangherate spremere ultimi carri trainati da asini e mendicanti. Veicoli da combattimento sono parcheggiate accanto alle capanne di lamiera ondulata dove i venditori vendono frutta e verdura. Sciita lutto le bandiere svolazzano nel vento. Ovunque gli scienziati si fermano, gli agenti di polizia unirsi a loro e aspettare educatamente fino a quando il guest dalla Germania ha riempito le provette.

Alberghi ed escursionisti

Alwash conosce il geologo da Freiberg, ei due uomini si salutano nel modo arabo, dal baciano su entrambe le guance. Ma gli Stati Uniti iracheno non condivide il pessimismo del suo collega tedesco. In realtà, egli vede il boom del petrolio come un'opportunità. "Forse siamo in grado di creare incentivi per le compagnie petrolifere di contribuire alla costituzione di una riserva naturale in cambio", dice Alwash.

Alwash non ha paura di sognare. E quando scivola attraverso le sue amate paludi in una barca durante la serata, il suo sogno sembra a portata di mano. "Vedo che galleggia hotel canneti e campeggi," dice. "Vedo kayak con fondo trasparente, escursionisti, appassionati di parapendio e mongolfiere." Le sue guardie del corpo lo ascoltano, le armi abbassate.

"Le prime persone a venire saranno i ornitologi," Alwash continua. "Allora le persone che sono interessate in archeologia, nelle antiche città di Ur e Uruk. E poi gli eco-turisti". Eco-turisti? Alwash sorride, e poi dice:. "Uno dei miei punti di forza è che io non mi lascio costretto dalla realtà".

C'E' UN PARCO IN PARADISO: RINASCE L'EDEN |

Web

Web